Jargon Junction: Balance Sheet

The bullshit on the left has to equal the bullshit on the right

A balance sheet is an important financial statement which lists a company’s assets, liabilities, and equity. I realize I just defined jargon with more jargon, which is not very insightful. Let’s dig in further.

An asset is something a company owns, which has “market value” and can be exchanged or converted into cash2. Assets on a company’s balance sheet include cash (obv), stocks, bonds, vehicles, heavy machinery, office buildings, manufacturing plants, land, etc.

A liability is something a business owes, which needs to be paid out or paid back. Liabilities include short-term loans and long-term debt, bills for goods, services, and utilities, employee bonuses, salaries, and pensions, deferred taxes, etc.

Equity is the difference between total assets and total liabilities, and reflects the “value” accrued to and owned by shareholders.

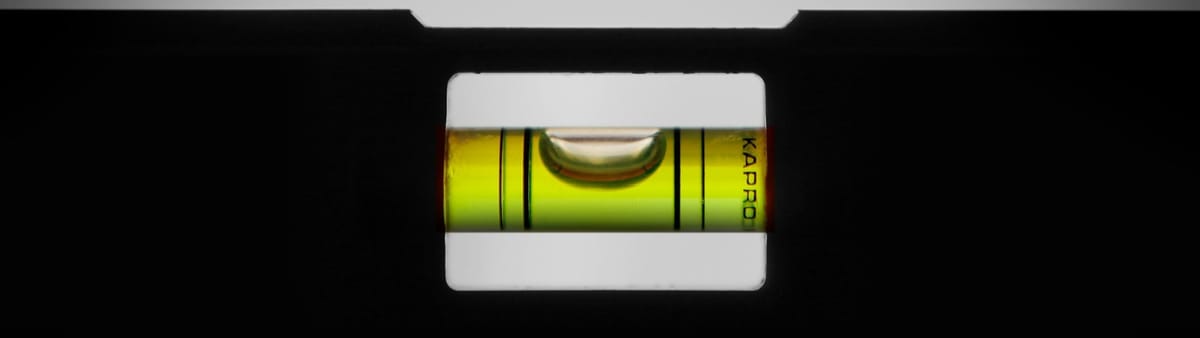

A balance sheet balances because the total assets are equal to the total liabilities plus the total equity, i.e., Assets = Liabilities + Equity.

Here’s another way to think about this relationship: if a company liquidated all of its assets, and settled all of its liabilities, the difference would be the equity owned by investors.

Seems straightforward, right?

It is, except there’s one major problem with a balance sheet: it only captures a single snapshot in time, and that snapshot is only published once per quarter. (There are several other issues, which I’ll skip for now.)

Let’s consider a very simple balance sheet.

Imagine you want to buy a $500,000 house, and you’ve saved $100,000 in cash for the down payment. Before you make this terrible decision, your balance sheet has $100,000 in assets (your cash), $0 in liabilities (you don’t owe nobody nothing), and $100,000 in equity (your cash).

Suppose you finalize this terrible decision on September 30 and file your balance sheet with the Securities and Exchange Commission. You report $500,000 in assets (the market value of your house), $400,000 in liabilities (your mortgage, or the portion of your house the bank “owns”), and $100,000 in equity (the portion of your house you “own”).

Assume the very next day, October 1, the housing market crashes and the value of your house plummets to $300,000.

What does your real-time balance sheet look like?

You have $300,000 in assets (the market value of your house), $400,000 in liabilities (the bank doesn’t give a shit about your problems), and negative $100,000 in equity (you’ve officially become less than worthless).

Of course, since you prepared and filed your documentation the day before, on paper everything still looks great.

What’s the takeaway?

Never buy a house.

Also, when you look at a balance sheet, remember it’s a static document and only reflects the business and market conditions on the day it was prepared.

Big multinational corporations are orders of magnitude more complex than the example I provided above, which means a once per quarter gander at their “consolidated” balance sheets may not represent reality.

Worse yet — and something we’ll get into in future issues — is every single accounting metric on a balance sheet is ripe for deception, manipulation, and fraud. This introduces additional layers of complexity into even the most rigorous financial analysis.